The following article represents one percent of the information in the book, Developing Lean Leaders at All Levels, by Jeff Liker and George Trachilis.

The teaching objectives for this section are to:

- Discuss the age-old question that Hoshin Kanri tries to solve.

- Discuss the history of Hoshin Kanri at Toyota Motor Company (TMC).

- Share the initial mechanics of setting up metrics for Hoshin Kanri.

VERTICAL AND HORIZONTAL ALIGNMENT

The age-old management question: How do you develop people with skills and motivation aligned toward a common vision?

I bet that you could find some Greek writings or even earlier–ten thousand years ago–where leaders are scratching their heads and saying, “Why don’t people do what I need them to do and do it well and do it with passion, and why won’t they listen to me? I am telling them what we need to do to be successful; why aren’t they doing it?”

Well, they’re resisting the change. People will naturally resist change. You might even think that they weren’t raised right, and they are lazy. Getting people to listen and follow is every leader wants; that’s the definition of being a leader is that you have followers, and they are all coming together toward your vision. So if I could get time with any CEO in the world and I would ask them, “Would you be happy if you decided what the business needed and everybody just jumped to attention, did a fabulous job executing, and they helped you deliver exactly what the business needed; would that be a good thing?” Well, they would probably kick me out of their office. They would think I was nuts to even ask the question. It’s what business is. It’s what an organization is: People aligned toward a common goal and working together.

If you responded to that same CEO and asked a follow-on question; “That’s great that you want that. How do you get it?” They will also probably have eloquent answers, but the answers will most likely be wrong. Because they’ll say, “Well I tell them what I need; I motivate them, and inspire them, and we have a very positive work environment; we treat our employees well, and I expect them to do a full day’s work for a full day’s pay and to work toward business goals.”

Again, that’s great, but how do you achieve it? It doesn’t really answer the question, “How do you achieve it?” It is assuming that if you have the right environment, and if the leaders make it clear what you need, somehow people will find a way to get it done.

What I’m going to argue–well this whole course is in fact about it–there is a set of skills needed for improvement that need to be deliberately learned like you deliberately learn any other skills. It doesn’t happen because of a charismatic leader who gives an impassioned speech and treats you well in pay levels and work environment. People need a structure to develop plans that align, and then they need the discipline, the skill level, the leadership level so they can make this happen on a daily basis¾make what needs to happen, happen. Only in this way plans actually get executed as they’re supposed to.

HOSHIN KANRI HISTORY AT TOYOTA

Figure 1. Jeff Liker shows a slide on the History of Hoshin Kanri

A little history: Let’s look at Toyota and how they came to discover and begin to use Hoshin Kanri; it goes back to 1961. See Figure 1. Hoshin Kanri already existed as part of Total Quality Management. At that time in the Toyota Motor Company – the master parent company of the automobile business – they had done a lot. By this time TPS had been developed within Toyota, and it was functioning quite well. They were beginning to teach their suppliers; some were highly developed in the Toyota Production System; others were still learning. They had a lot of smart, hardworking people, but TMC still realized that they were not a modern global company; they were a really good local company. If they wanted to achieve their goal – to be a successful as an automotive company – skills were needed, and skills came from globalizing, not from building to their own small client base.

They decided that they needed to modernize their operations. Eiji Toyoda, the cousin of founder Kiichiro Toyoda, established two fundamental needs. One was that top management, in particular, needed to be able to clarify targets. Remember, Toyota was not competitive in quality at that time. Their quality was getting better, but there was a big gap with the American auto makers. Toyota needed to clarify the targets for quality and they needed to engage employees. Clarifying targets didn’t mean Eiji needed to polish up his speech as a President and make his speech clear. He needed to have metrics–targets which were meaningful to people doing the work–not just waving his hands and saying, “We need Quality. We need Quality. We need fewer defects.” You could measure that, right. “We need fewer defects which translates to higher customer satisfaction; with satisfaction surveys, we can measure defects.”

I am in the Stamping Department, stamping body parts and saying, “So what is it you want me to do? We have the defects measured; we know how many defects we create inside the factory; we know many defects are getting to the customers; we know that they’re not satisfied with the body; there’s too much air noise leaking through; we know all these things; what am I supposed to do? What am I supposed to work on?”

So it becomes obvious that the measuring of defects by itself is too global to really help anyone at the local level define their actions. Then Eiji also knew that even if he could do number one well, it wasn’t going to work unless he could promote cross-functional cooperation. There’s Quality, Human Resources, Information Systems Division; I guess they didn’t have computers at that time, but people were defining the information flow for materials. There were all these different groups, and they all needed to work together to achieve Quality.

After the review of the alternatives, Toyota discovered Hoshin Kanri in the 1960s and began to implement it with a more concrete goal than simply, “We want good Quality.” The concrete goal was: “We want to win the Deming prize.” Deming had been around for quite a while, and he was the Quality guru in Japan. Dr. Deming taught Statistics Process Control; he taught that you need built-in Quality, not inspected Quality. He was highly regarded by Toyota, and they established a prize in his name which was extremely tough to win. Competition was very tough in Japan, and Toyota decided, “We’re going the win the Deming Prize for Quality as a concrete target for focusing our efforts as a company.”

ALIGN METRICS FROM TOP TO BOTTOM

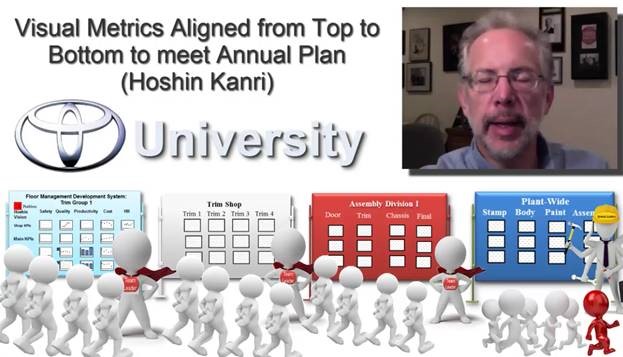

Figure 2. Jeff Liker explains the importance of Visual Metrics

One of the early things that you can do when you want to start to get people aligned, is post aligned metrics out on the floor. We’ve already talked about the importance of visual metrics in the last section on Self-Management and Work Groups. We talked about how work groups need to meet some place and be able to visualize the problems and step by step develop plans for improvement. See Figure 2. Management should be coming around and checking on process, the people, and how they’re doing at achieving the metrics. The metrics provide the starting point. What’s our target? Where are we? Where are we red? It is necessary to recognize the gap between the target and the actual. Then you can begin coaching.Here is an example. During the recession I visited Toyota’s plant in Indiana, and they had been operating for about eight years making trucks and mini vans and large sport utility vehicles. In the process they are winning Quality award after Quality award. During the recession, they needed to shut down for three months because they had too many trucks, and demand had dropped so much. They were operating at about 60% capacity for six to seven months. During that time, they didn’t lay off regular employees, but they basically turned the plant into a university to teach the Toyota Production System for three months, and people were working half time and they were learning half time. One of the things they focused on was teaching Hoshin Kanri, using the Floor Management Development System, which we talked about in the last section.

This was a system getting people to meet every day, to identify problems, to work toward a target, and again do Kaizen every day in these small loops PDCA, PDCA, PDCA. They have these new white boards that they called the Floor Management Development System board; they were developed about ten years earlier, and they were teaching people to follow Toyota Business Practices, which we talked about as Toyota’s eight-step problem solving method. They were acting as though this was new; I’d been seeing it for ten years around Toyota. I was confused; why was this great plant that won Quality awards talking about Hoshin Kanri and the Floor Management Development System as if it were a new plan developed yesterday, when it had existed as system in Toyota for decades.

The answer was; they had been engaging employees in Kaizen; in fact, some of the hourly workers were better than managers at Kaizen. It was not a question of people not knowing about Kaizen. They knew how to use the tools for improvement. That was not the case; they were good at it. What they had never done because of their success and selling so many vehicles, so many trucks¾ they were making so much money that they didn’t take the time to systematically put in the whole process of Hoshin Kanri. This was missing for true alignment throughout this plant. At that time they were doing that because we had the time; they had gone three months without even making trucks; now they had even more time since the recession was lingering on.

Managers brought the Floor Management Development System boards to the shop floor. They had boards; they had metric boards; but they were not aligned. The Floor Management Development System board worked, the top line only. For example, if you were in assembly and you’re assembling part of the trim on the vehicle- in your group with a group leader – at the top level you might have Safety, Quality, Productivity, Cost, Human Resource Management. Those were the standard categories, and this year your management has signed up for targets needed by the President of the company. If every part of the company achieves their targets, the President would achieve the corporate targets.

That’s at the top line, and as I said, reducing defects is a generic measure. Productivity of labour hours per vehicle is a generic measure. If the numbers go down, you’d have to make the target relative to that. Say that you’re in the Trim Department; you’re doing assembly; what is it that you can do to improve Quality? You don’t have a lot of equipment, so you don’t need to do a lot of preventative maintenance; you don’t need to change the tools regularly; it’s a labour-intensive operation. So you need to figure out what are the causes were, and a common approach to doing this is using the 5-why process. Why do we have these defects? Get even more specific. Why do we have the defects that you are producing right now? It could be scratches and scrapes, and that leads you in one direction. Or it could be that the parts aren’t fitting correctly, and the bumpers kind of separated from the bodies, and there are gaps; that’s a different problem. So, based on the problems, we will figure out what we’re going to measure, for example, the size of gaps between the bumper and the steel. Then we’re going to find what processes cause that more than others; this way we can begin to focus on those processes to develop Performance Indicators for the processes that are causing the most trouble. As a starting point, and we’re going to put that data up on the board.

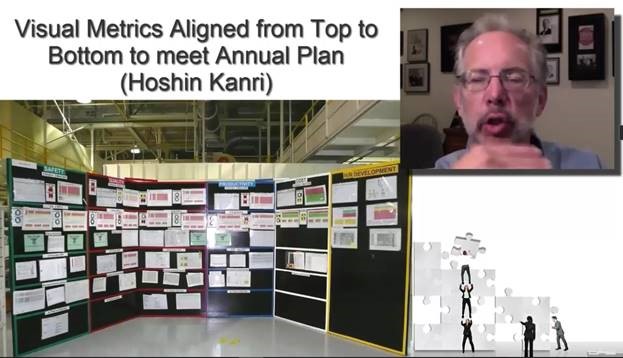

Figure 3. Visual Metrics Aligned from Top to Bottom

There are also areas on the board at the bottom. See Figure 3. Usually you’ll see A3 reports that are the problems being worked on to improve the Quality of this process that’s causing trouble. That may be in the form of a very specific A3, where you analyse the current situation; you have a desired output, and you’re finding ways; you’re doing things, and you’re finding ways to improve that particular process. The board, goes from top to bottom; at the top are the most general measures that align to the goals of the plant, and at the bottom are very specific actions that you’re taking to improve the process.

Now this is happening at every stage in the plant. The manager of the Trim Shop has a bunch of group leaders, and each group leader is individually doing the same thing. They’re trying to meet the numbers, for example, the defect reduction levels that the Trim Shop manager has signed up for, and the Trim Shop manager is checking all four of the group leaders in their areas and she is walking around, looking at the boards, coaching them to achieve what she has committed to for the General Manager, who runs all of Assembly Division I.

The Toyota plants often will have two different Assembly lines; they do that in Indiana, and then the Plant Manager is looking at body and Stamping and assembly and at each level, they’re having a meeting of their subordinates. All the Managers meet with the General Managers; all the General Managers meet with the Plant Managers daily, on a daily cadence. Now you have an aligned set of boards, and let’s say the first thing that you can do is decide what your categories are for metrics; you can identify your Key Performance Indicators; you can begin to collect data; you can set targets for improvement. This is the mechanical side of Hoshin Kanri. You want the process to be visual because you want groups of people standing around looking at it, talking about it.

I’ve seen people use large plasma screens to do this, and that can be effective, but one thing nice about a board with papers is you can take out a pen and mark it up.

One-Minute Review

- How do you develop people toward a common vision? This is the age-old management question.

- Most of today’s CEOs would answer this question wrong.

- Most CEOs assume that by having the right environment, people will get it done.

- There is a set of skills that must be learned in order to make it happen.

- Toyota discovered Hoshin Kanri in 1961, and it had already existed as part of Total Quality Management in Japan.

- They needed to clarify their targets and to engage employees to work cross-functionally in order to become a global giant.

- The mechanical part of Hoshin Kanri is aligning metrics from top to bottom.

- On a daily basis each level meets with their subordinates, and this daily cadence is a key component to the organization of the boards.

******************************************************************

Each of these articles can be found on Kindle, and as an audiobook in Audible under the title, DEVELOPING LEADERSHIP SKILLS.

All 75 learning articles is crafted together in the book, Developing Lean Leaders at All Levels: A Practical Guide, authored by Jeff Liker with George Trachilis. The book received the SHINGO RESEARCH AWARD.

George Trachilis (left) and Jeff Liker receive the Shingo Research Award in Washington, D.C. (2016)